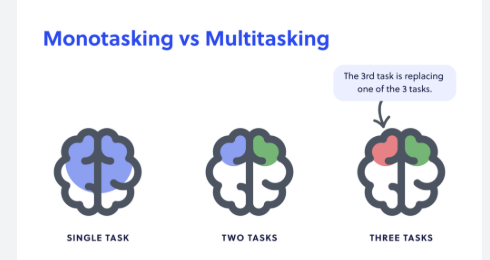

For meaningful work, single-tasking (one thing at a time) almost always wins. Research shows that frequent task-switching slows you down, increases errors and stress, and shortens focus spans. Multitasking only helps when the tasks are simple and don’t compete for the same mental resources.

Why our brains struggle with multitasking

What most of us call “multitasking” is actually rapid task-switching. Your brain toggles attention from A → B → A, paying a hidden “switch cost” each time. Classic lab work and real-world studies consistently show that when people juggle tasks, performance drops on one or both tasks—either they take longer or make more mistakes (and often both).

One influential Stanford study compared heavy media multitaskers with light multitaskers. The heavy multitaskers were more distractible, showed poorer memory, and performed worse at task-switching—precisely the opposite of what you’d expect if practice made them better at juggling. The takeaway: frequent multitasking correlates with weaker filtering of irrelevant information and poorer cognitive control.

The real cost of interruptions (and “just checking”)

Also Read : Digital Cleanup Day – Turning Your Phone and Laptop into a Productivity Machine

You don’t just lose the seconds you spend glancing at a message—there’s a re-orientation penalty before your brain is fully back in the groove. Field studies of knowledge workers have found that after an interruption, people often need on the order of ~23 minutes to resume the original task flow, and they report higher stress and time pressure on days with more switching. That re-focus delay compounds across a workday.

Meanwhile, our attention windows on screens have shortened dramatically. Longitudinal research led by Gloria Mark shows the average time spent on a single screen before switching is ~47 seconds (down from a couple of minutes in the early 2000s). Shorter focus bouts mean more switching and more cumulative costs.

When (if ever) multitasking helps

Not all “two-things-at-once” is bad. Multitasking can be fine when one task is automatic (e.g., folding laundry) and the other is low-load (e.g., listening to a podcast). Problems arise when both tasks draw on the same mental systems (e.g., two language-heavy tasks, or two tasks needing working memory and decision-making). In those cases, your brain must constantly arbitrate, and performance falls.

The productivity case for single-tasking

1) Faster, with fewer errors. By removing switch costs, single-tasking improves throughput on complex work. Even small switch penalties add up: a few dozen pings and checks can burn a surprising chunk of your day.

Also Read :The First 60 Minutes Rule – How to Start Your Day Like High Achievers

2) Deeper thinking and better memory. Focused work supports consolidation in memory and clearer reasoning. Heavy multitaskers show weaker filtering and memory on cognitive tasks, suggesting an attention “tax” that accumulates.

3) Lower stress and higher satisfaction. Studies of interrupted work show people feel more rushed and stressed when switching frequently—even when they try to “speed up” to compensate. Single-tasking reduces that cognitive friction.

Action plan: how to do single-tasking in a multi-tasking world

A) Time-block your day. Reserve 60–120 minute blocks for your highest-value task. Protect these blocks like meetings: close chat/email, silence notifications, and set your status to “heads-down.” Time-boxing and deep-work methods are built on single-tasking and are consistently recommended because of our cognitive bottleneck.

B) Batch messages. Handle email/DMs in 2–4 scheduled windows instead of reacting all day. Research on workplace communications shows that batching interruptions helps reduce stress and perceived overload while preserving responsiveness.

C) Use friction to your advantage.

- Keep your to-do list visible and pick one next action.

- Work in full-screen mode; keep only essential tabs open.

- Enable “Do Not Disturb.”

- If you must check messages, finish the current micro-step first (complete the sentence, run the test suite, save the file) to create a stable pause point—this cuts the re-entry penalty.

D) Design your environment. Noise-canceling headphones, a minimal desk, and a clean digital desktop reduce temptations and help attention stay “sticky.” Short, planned breaks (5–10 minutes) every 60–90 minutes refresh your focus without inviting random context switches.

E) Track and adjust. For one week, log: (a) number of context switches, (b) total focus minutes, and (c) tasks finished. Most people see a 20–30% bump in finished work simply by removing ambient switching—not by working longer.

What about creativity?

Some fear that single-tasking stifles creativity. In practice, alternating between deep focus and deliberate mind-wandering (walks, analog breaks, white-space time) works best. The key is intentional alternation, not reactive switching triggered by notifications.

A quick decision guide

- Is either task cognitively heavy (writing, coding, analysis)? → Single-task.

- Are both tasks language- or memory-intensive? → Single-task.

- Is one task automatic (walking, chores) and the other passive (podcast, music)? → Light multitasking is okay.

- Are you in a high-stakes context (exams, client calls, driving)? → Never multitask.

Bottom line

For routine, low-load activities, multitasking won’t hurt. But for anything that matters—learning, planning, writing, designing, coding—single-tasking wins on speed, quality, and sanity. Protect focus, batch the rest, and watch your output climb.

FAQS

Q1: Is the “8-second attention span” real?

That viral stat is disputed; stronger research finds ~47-second average focus on a screen before switching (2016–2023 observations).

Q2: How long does it take to recover after an interruption?

Field studies report around 23 minutes to fully resume the original task context; people also report higher stress on heavily interrupted days.

Q3: Can I train myself to be a better multitasker?

Evidence suggests heavy media multitaskers become more distractible, not better at switching. Training attention and designing your environment for single-task blocks is more effective.